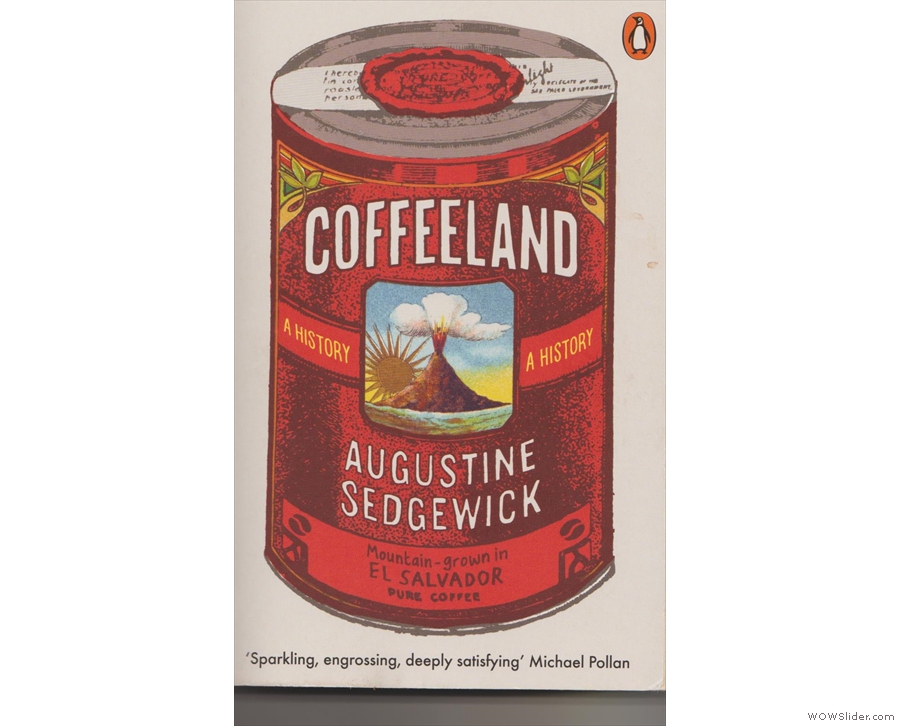

Regular readers know that I don’t often write about coffee books, so today’s Saturday Supplement is the exception that proves the rule. Coffeeland, by Augustine Sedgewick and published in 2020 by Penguin Books, was a chance discovery in my local bookshop while I was looking for something else (Howul, if you’re interested, an excellent debut novel by my friend David Shannon).

Regular readers know that I don’t often write about coffee books, so today’s Saturday Supplement is the exception that proves the rule. Coffeeland, by Augustine Sedgewick and published in 2020 by Penguin Books, was a chance discovery in my local bookshop while I was looking for something else (Howul, if you’re interested, an excellent debut novel by my friend David Shannon).

Back to Coffeeland: I hadn’t previously heard of the author, and was completely unaware of the book, but there it was, sitting on the shelf. I was intrigued by the title, so picked it up, read the blurb on the back and made the impulse decision to buy it.

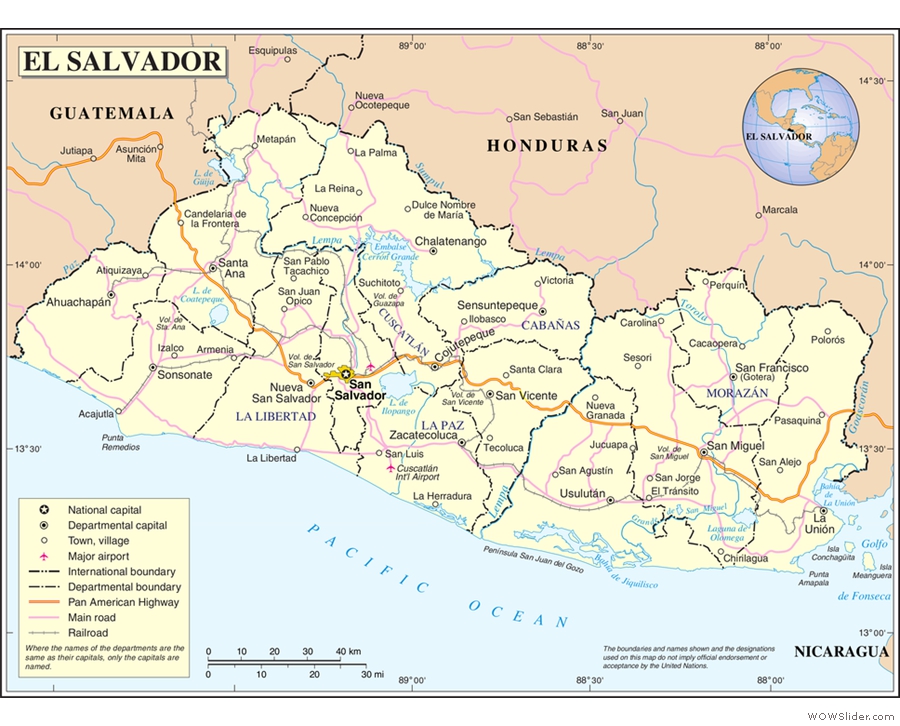

Coffeeland is ostensibly a history of coffee in El Salvador (the “coffeeland” of the title), with the focus on James Hill, who went from the slums of nineteenth-century Manchester to El Salvador, where he founded one of its great coffee dynasties. However, Coffeeland is a lot more than that, a fascinating, multi-threaded book which weaves together many strands of the modern, industrial world to tell the story of coffee from the perspective of those who produce it. A harrowing read at times, it shines a light on some of coffee’s darker corners.

You can read more of my thoughts after the (very short) gallery.

Coffeeland is a densely written, but easy reading 360-page paperback, with another 70 pages of notes and indices, a testament to the depth of research that went into its writing, a process that took over 10 years. At its core, it tells the story of James Hill and the subsequent generations of his family who became one of the leading coffee producers in El Salvador, starting with James’ childhood in the industrial slums of Manchester.

However, it’s about El Salvador, a country of which I knew very little before reading Coffeeland. It shows how El Salvador’s history is inextricably entwined with that of America, of how the American demand for coffee pushed production in El Salvador and other central American countries and how coffee production there influenced American tastes.

On a wider scale, it’s a tale of imperialism, capitalism and revolution, as well as one of exploitation. I learnt so much from reading Coffeeland, including many aspects of coffee production that I’d never even given thought to. Coffee production in El Salvador involved a steady consolidation of the means of production into fewer and fewer hands as the leading coffee-producing families, the Hill family amongst them, bought up their smaller rivals.

While the winners of this consolidation were the coffee-producing families, the losers were the people of El Salvador. El Salvador had once been a land of plenty, where families could live on the land. However, people who can support themselves have little incentive to carry out the back-breaking work required on a large coffee plantation, from the digging of holes for new trees to the harvesting of the ripe coffee cherries.

While the coffee plantations did provide employment, they did so largely by removing the ability of the population to support itself, thus forcing them to work, often for long hours and little pay. Food was at the heart of this system: as land was increasingly concentrated into the hands of the few and coffee cultivation spread, so families lost the means to support themselves.

The cruellest part of this were the changes in the coffee plantations themselves. Traditionally coffee grew in the shade of fruit-bearing trees, with ground cover provided by vines and bushes bearing berries and fruit, all of which the workers could eat. But James Hill needed his workers hungry, so that they would come to him for food. By controlling their access to food, he could control their productivity, so he cut down the fruit trees and tore up the cover plants.

Another fascinating aspect was the role of San Francisco in developing what are known as mild coffees, where the emphasis is on taste. While the east and gulf coast ports of New York and New Orleans focussed on Brazil, San Francisco and the west coast turned its attention to Central America. Leading players in this new coffee industry were the Hills brothers (no relation to James Hill) who originally came from Maine. They pioneered vacuum-packing coffee in tin cans, promoting the taste of their coffee and focusing on quality rather than price. They were instrumental in changing how coffee was evaluated, moving the industry away from judging the quality of coffee by how it looked to how it tasted, introducing the cupping methodology that the coffee industry still uses today.

I could go on, but instead I’ll point you towards Coffeeland if you want to know more. It’s a thoroughly researched, well-written and illuminating read. I cannot recommend it highly enough.

If you liked this post, please let me know by clicking the “Like” button. If you have a WordPress account and you don’t mind everyone knowing that you liked this post, you can use the “Like this” button right at the bottom instead. [bawlu_buttons]

Don’t forget that you can share this post with your friends using buttons below.

1

1 2

2 3

3 4

4

Pingback: Bean and Hop | Brian's Coffee Spot

I read most of this book before I had to return it to the library. I did learn a lot about coffee production, imperialism and more on topics not coffee related. Thanks!