Since there is a dearth of coffee shops that I can write about at the moment, I’m branching out a bit to write about books instead. So welcome to the first of four posts about the British Library’s Philosophies series. Astute readers will realise that this is a little self-serving since I wrote one of the early books in the series, The Philosophy of Coffee. However, since I’m now selling the rest of the (food-related) titles on the Coffee Spot, I thought I should say something about them, starting The Philosophy of Cheese.

Since there is a dearth of coffee shops that I can write about at the moment, I’m branching out a bit to write about books instead. So welcome to the first of four posts about the British Library’s Philosophies series. Astute readers will realise that this is a little self-serving since I wrote one of the early books in the series, The Philosophy of Coffee. However, since I’m now selling the rest of the (food-related) titles on the Coffee Spot, I thought I should say something about them, starting The Philosophy of Cheese.

The Philosophy of Cheese is, like all the books in the series, a compact volume, packed with interesting, entertaining facts. It might seem a strange choice (The Philosophy of Tea is a more likely first bedfellow), but the truth is, I really like cheese, so it was the first one I reached for. I usually have five or six cheeses in the house at any one time (currently I have Cheddar, Stilton, Bree, Gorgonzola, Mozzarella and Parmesan) and quite often pair cheese with coffee (a really mature bree, the sort that’s just about ready to crawl off the plate, goes really well with espresso, for example).

You can see what I made of The Philosophy of Cheese after the (very short) gallery.

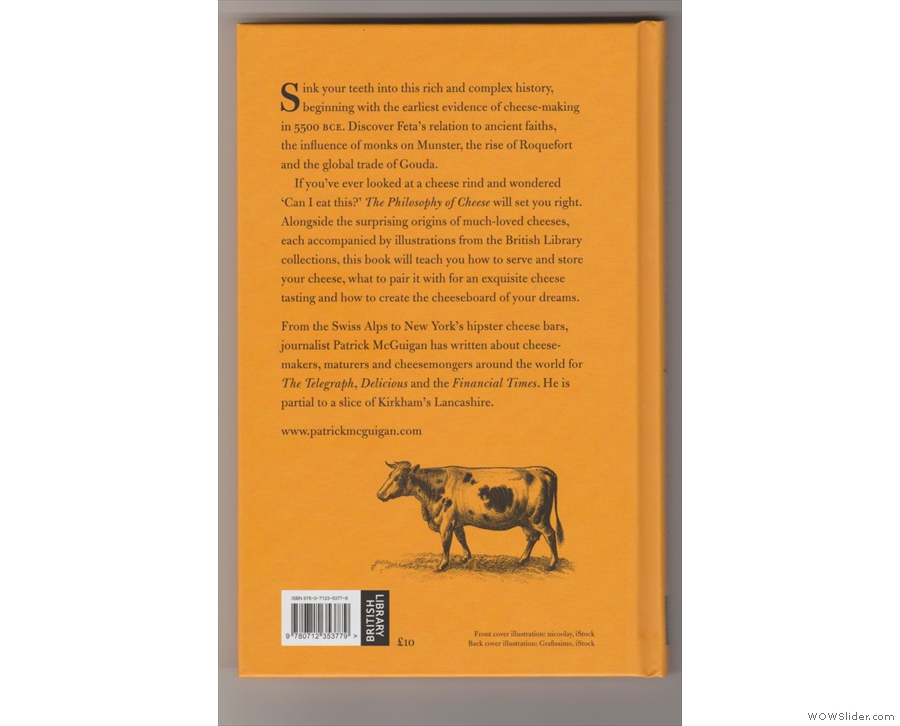

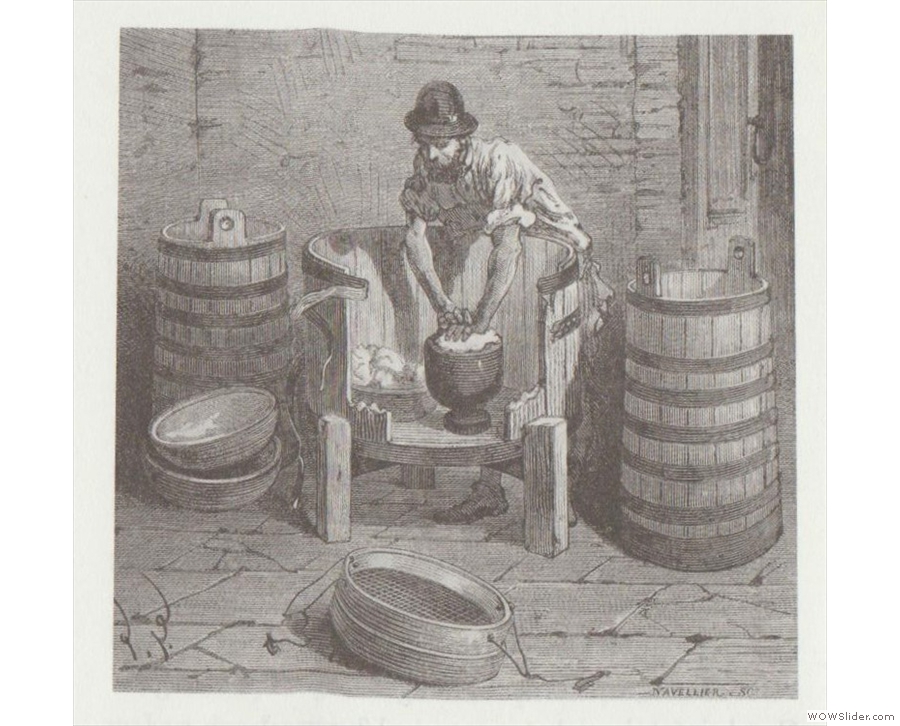

When I wrote The Philosophy of Coffee, one of the things that struck me is just how young coffee is, having first been drunk around 1,000 years ago. Cheese, on the other hand, has a much longer history. We think that cheese, in a form we would recognise, has been for a long time, with the first archaeological evidence for cheese-making being dated to 7,500 years ago.

Since then, cheese has been on quite a journey, a story which The Philosophy of Cheese tells, starting with short chapters on the pre-history of cheese and how it is made. Along the way, we come across plenty of cheese origin myths, with the author, Patrick McGuigan, broadly reaching the same conclusions that I did about the various coffee origin myths: while they are entertaining stories, and might contain a grain of truth, they are to be taken with a pinch of salt (and often a whole handful).

Although cheese is a global phenomenon, with cheese-making probably independently developing in various locations throughout history, The Philosophy of Cheese focuses on the history of a handful of European cheeses. While I’d love to have heard about cheeses from other parts of the work, in such a slim volume, these sorts of compromises are inevitable (for example, the hardest part of writing The Philosophy of Coffee was deciding what to leave out).

Our journey starts with Feta and Pecorino, which can trace their roots back to Ancient Greece and beyond (Feta) and the Roman Republic (Pecorino). Having dealt with these venerable cheeses, The Philosophy of Cheese moves into the Middle Ages with some of Europe’s most famous cheeses. What I hadn’t realised is the central role that religious orders played in their creation: Munster, Parmigiano Reggiano, Brie and Roquefort all have close associations with monasteries, some of which can trace their roots back around 1,000 years!

These cheeses continue to be made in the same locales, using the same production methods to this day, a result of the Protected Food Names scheme and its forerunners, which are both a blessing and a curse. On the one hand, they protect a brand and its values, as well as keeping old traditions alive. On the other hand, by restricting where and how a cheese can be made, down to what milk can be used and what the livestock can be fed, it can stifle innovation.

Compared to the ancient monastic cheeses, Gouda, a Dutch cheese, is a relative newcomer, as are the British cheeses, Cheshire and Cheddar, the last of which brings the tale up to the modern day. Cheddar was once a farmhouse cheese that was rarely seen outside its native county of Somerset. However, as the 19th century went on, cheese production became more efficient, but it was really the Americans, through Xerxes Willard who took this to the next level.

The first cheese factory opened in New York State in 1851. By 1899, America had 1,500 cheese factories, mostly making Cheddar (which didn’t benefit from any protection). The UK began to import American cheese and by 1913, it was estimated that 80% of the cheese consumed in the UK was imported to the detriment of homegrown farmhouse producers. This trend was accelerated by the two world wars. In 1939, there were 514 farms producing cheese in the southwest of England. By the end of the war, there were just 57.

It is only in recent years that this trend has begun to be reversed. The Philosophy of Cheese brings the story to close on a positive note by returning to America and Rogue River Blue, a cheese from Oregon. In 2019 it won the coveted Best Cheese in the World Award, illustrating the rebirth of farmhouse cheesemaking through the growth of the artisan cheese movement which continues to this day.

The book closes with some practical notes on how to construct a tempting cheeseboard, a fitting place to end. Now, where did I put my cheese?

Next in the series, I take a look at The Philosophy of Tea.

Don’t forget that you can share this post with your friends using buttons below, while if you have a WordPress account, you can use the “Like this” button to let me know if you liked the post.

1

1 2

2 3

3 4

4 5

5

Pingback: The Coffee Spot in 2021 | Brian's Coffee Spot

Pingback: The Philosophy of Tea | Brian's Coffee Spot

Pingback: The Philosophy of Wine | Brian's Coffee Spot

Pingback: The Philosophy of Gin | Brian's Coffee Spot