Welcome to another in my series about the British Library’s Philosophies series. Today it’s the turn of The Philosophy of Gin by Jane Peyton, the second in the series, after The Philosophy of Wine, to feature alcohol. I’ve timed today’s piece to coincide (roughly) with the publication of the third book in the series to feature alcohol, The Philosophy of Beer, which actually comes out tomorrow (8th April) and is by none other than Jane Peyton!

Welcome to another in my series about the British Library’s Philosophies series. Today it’s the turn of The Philosophy of Gin by Jane Peyton, the second in the series, after The Philosophy of Wine, to feature alcohol. I’ve timed today’s piece to coincide (roughly) with the publication of the third book in the series to feature alcohol, The Philosophy of Beer, which actually comes out tomorrow (8th April) and is by none other than Jane Peyton!

Like the others in the series (The Philosophy of Wine, The Philosophy of Cheese, The Philosophy of Tea and my own book, The Philosophy of Coffee), The Philosophy of Gin is a compact volume, packed with interesting, entertaining facts. Indeed, its bite-sized chapters are just the right length to be read while sipping a Gin & Tonic (G & T).

More than any of the other books in the series, The Philosophy of Gin has a very British focus, gin being a quintessentially British drink, although there’s a nod to the Dutch (who introduced its forerunner, genever, to London) and the Americans (who popularised gin cocktails and, thanks to prohibition in the 1920s, sent all their best mixologists to Europe!).

You can read about that and a whole lot more after the (very short) gallery.

So far, when writing about wine, cheese and tea, I’ve had to start by contrasting their 1,000s of years of history with coffee, which, at around 1,000 years old, is the comparative new kid on the block. So, it comes as something of a relief that I don’t have to do that with gin, which manages to make coffee look venerable. Gin, you see, is only a few hundred years old, having evolved in London in the late 17th century.

Now, in fairness, humans have been distilling alcohol for thousands of years, while they have been experimenting with adding juniper (a key component in gin) to distilled wine for at least 1,000 years. Gin itself evolved from genever, a juniper-flavoured spirit which had been produced in the Netherlands since the late 16th century. It became popular in London partly due to the Glorious Revolution of 1688, when Prince William III of Orange invaded England, deposed his father-in-law, King James II, and put James’ daughter, Mary, on the throne.

That’s how gin got going in London, but what exactly is it? It all starts with the fermentation of plant materials (typically fruit or cereal) to produce what’s known as the wash, which is then distilled to concentrate its alcohol content. This base spirit, which has almost no flavour, is then redistilled in the presence of juniper and other botanicals, the juniper giving the resulting gin its characteristic taste and the other botanicals (craft distillers will use as many as 20 different botanicals for a particular gin) adding that gin’s specific flavours.

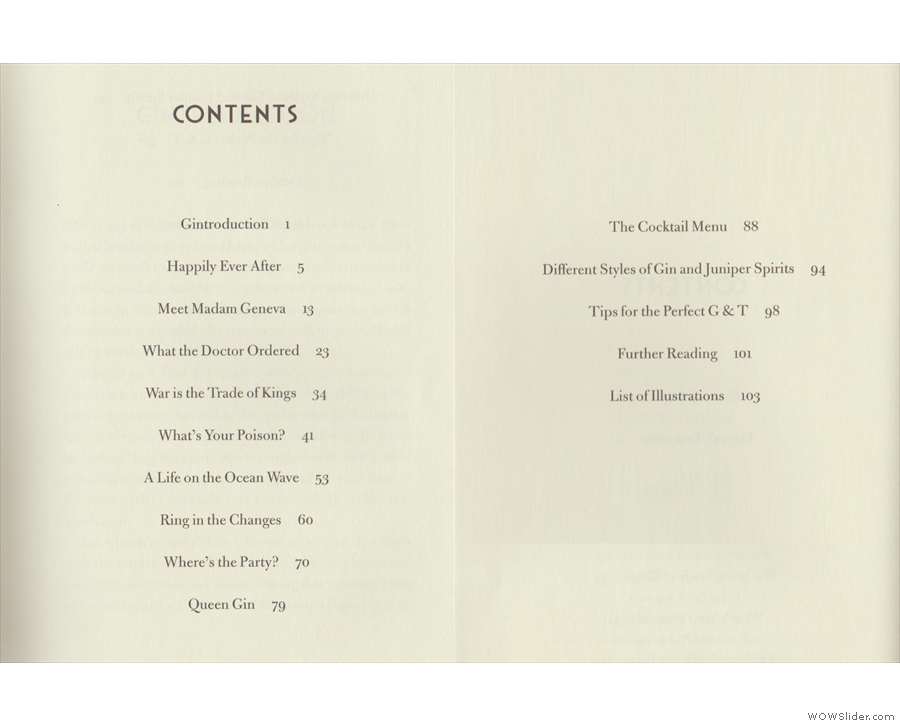

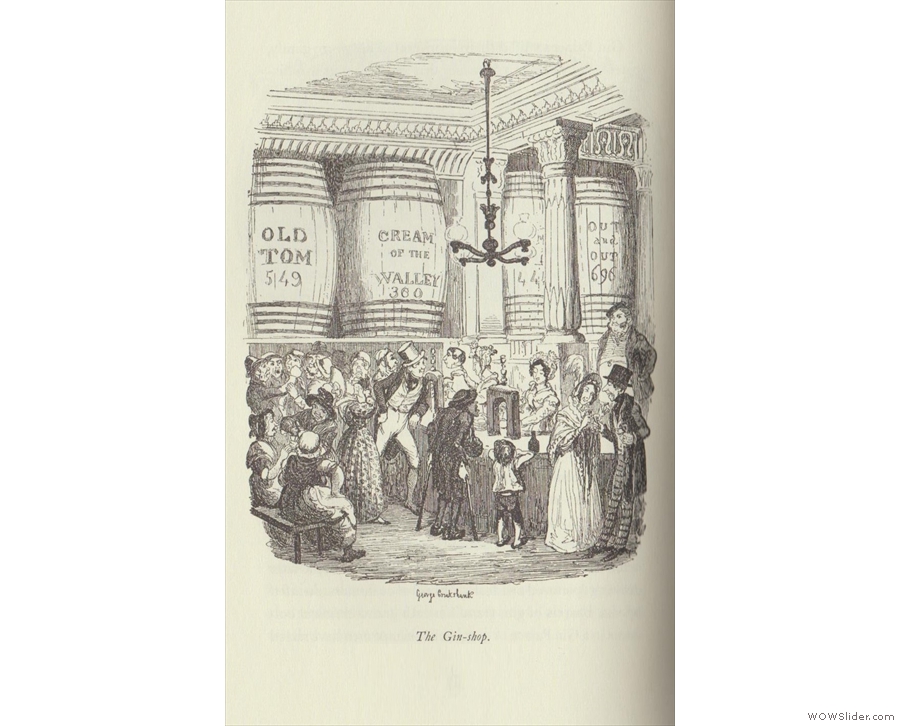

All of this is covered in the opening chapters of The Philosophy of Gin, along with its roots as a medicinal drink. From there, Jane Peyton takes us through its rise in popularity, partly driven by King William’s decision to increase duties on beer and imported spirits, while at the same time reducing the tax on spirits distilled from British grain. This led to a boom in gin consumption, gin becoming associated with the urban poor, particularly in Britain’s port cities.

Gin was originally drunk neat, but its partnering with other ingredients led to its wider acceptance as a social drink. In the early 19th century, sailors in the Royal Navy were mixing their daily dose of lime juice (to combat scurvy) with gin, creating the Gimlet cocktail. Similarly, colonists in the tropical regions of the British Empire added gin to tonic water (which contained quinine to ward off malaria), thus creating the G & T.

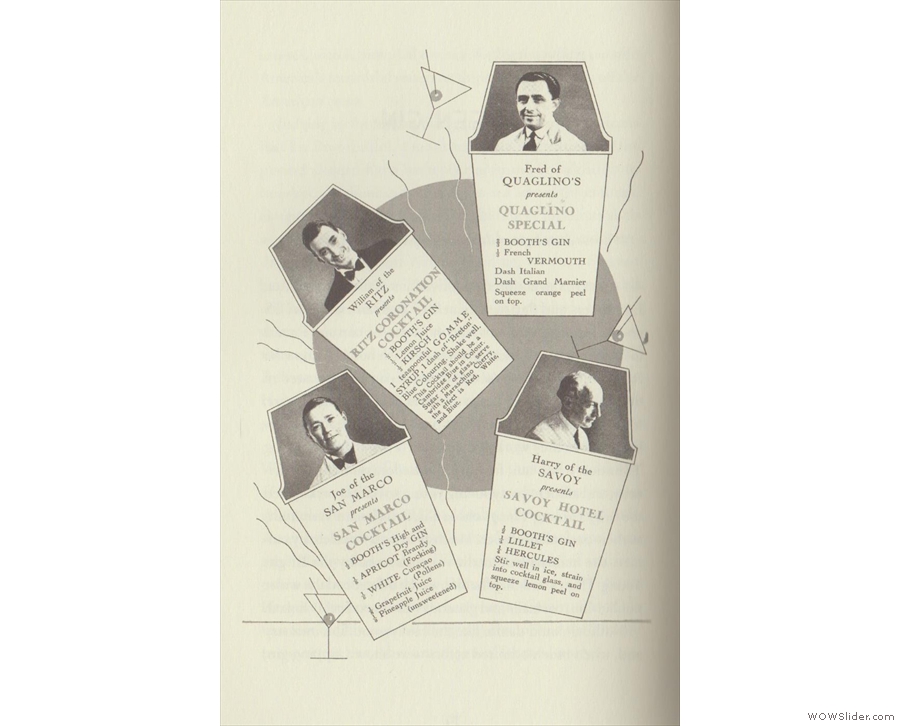

Developments in distilling technology in the 19th century increased gin’s popularity, which received a further boost in popularity when phylloxera devastated European (and especially French) vineyards from 1862 onwards. The British had taken gin to America, where it proved popular in cocktails, which were all the rage at the start of the 20th century. However, prohibition, which came into force in 1920, drove many of America’s best mixologists to Europe, further boosting the popularity of cocktails, in particular the martini, on this side of the Atlantic.

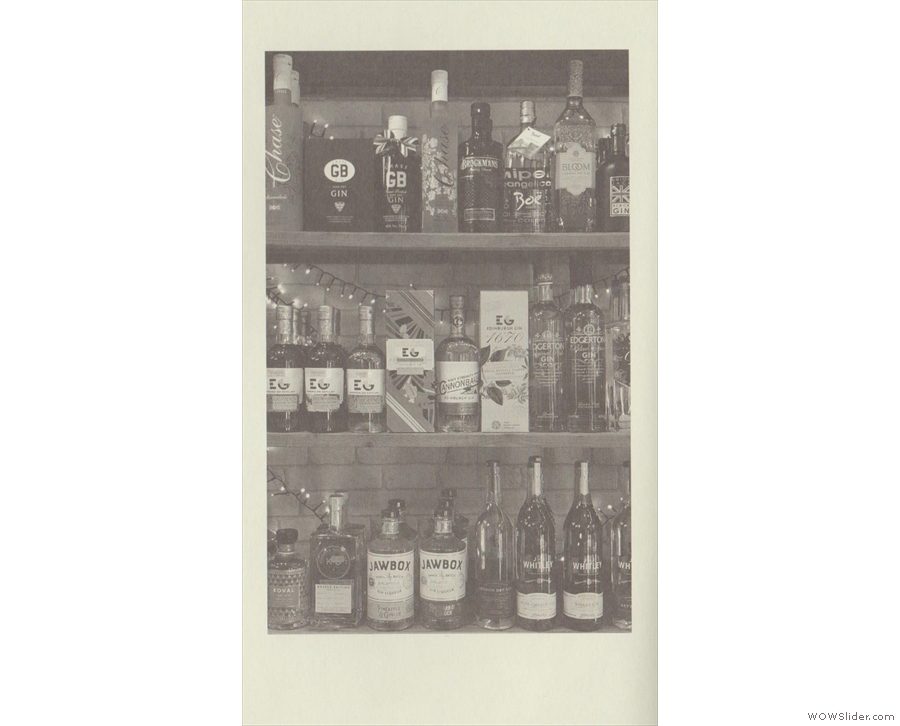

However, gin’s popularity waned after World War II, its image becoming associated with older drinkers, with vodka replacing it as the spirit of choice amongst the young, helped, no doubt, by the screen version of James Bond drinking vodka martinis. It could have been a very sad end for gin, but instead it came roaring back in the late 20th century, first fuelled by the big distillers and then, more recently, by the explosion of craft distillers following a 2009 change in the law (in Britain) to allow smaller stills.

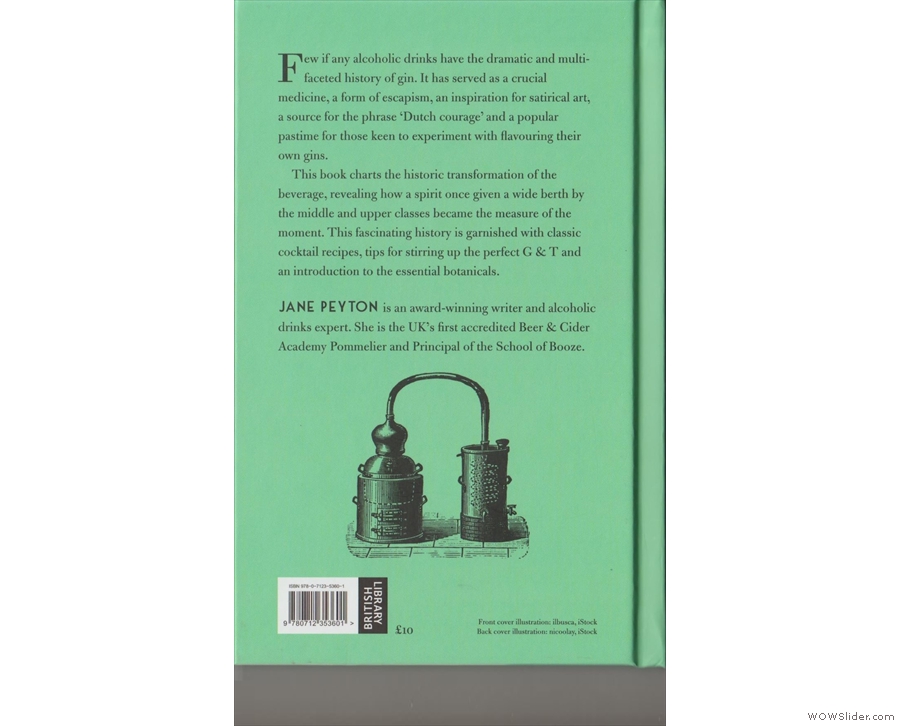

The Philosophy of Gin ends on this high note, finishing with a round-up of recipes for all the cocktails mentioned in the book, plus tips for the perfect G & T.

Don’t forget that you can share this post with your friends using buttons below, while if you have a WordPress account, you can use the “Like this” button to let me know if you liked the post.

1

1 2

2 3

3 4

4 5

5 6

6