Welcome to the third in my series of four posts about the British Library’s Philosophies series. Having covered The Philosophy of Cheese and The Philosophy of Tea (as well as my own book, The Philosophy of Coffee), I’m moving onto The Philosophy of Wine, the first of the series that deals with alcohol.

Welcome to the third in my series of four posts about the British Library’s Philosophies series. Having covered The Philosophy of Cheese and The Philosophy of Tea (as well as my own book, The Philosophy of Coffee), I’m moving onto The Philosophy of Wine, the first of the series that deals with alcohol.

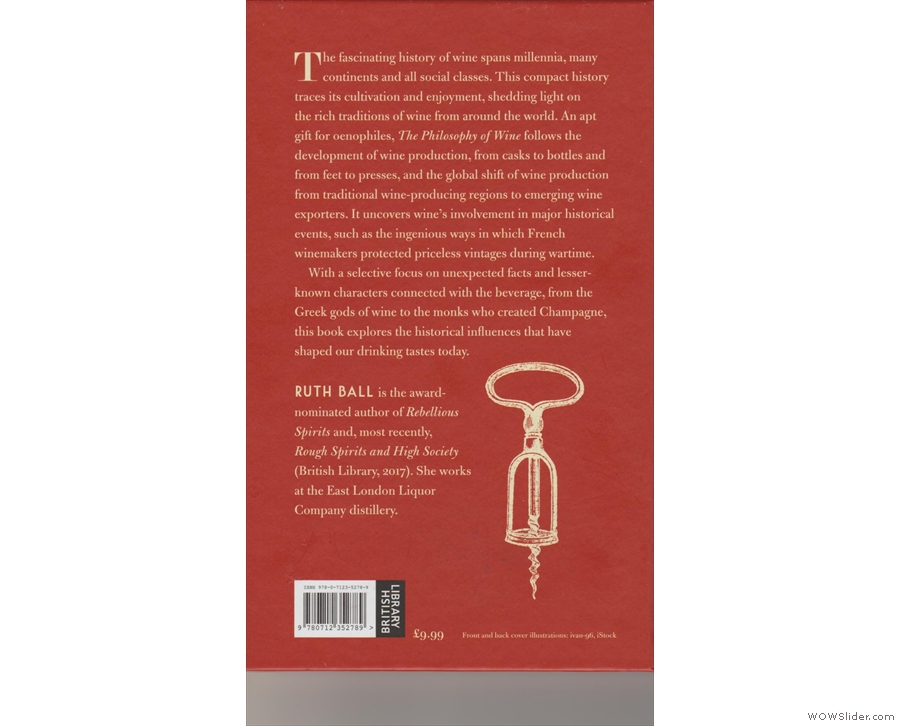

Like its siblings, The Philosophy of Wine is a compact volume, packed with interesting, entertaining facts. Indeed, its bite-sized chapters are just the right length to be read while sipping a glass of wine (or two).

The only problem about writing such a concise book is that wine has such a rich and incredible history that there’s no hope of squeezing it all in, even at the highest level. I thought I had problems deciding what to leave out of The Philosophy of Coffee, but Ruth Ball, author of The Philosophy of Wine, had it ten times harder!

You can see how Ruth managed it after the (very short) gallery.

Like tea and cheese, and in distinct contrast to the new kid on the block, coffee, wine has been around for a very long time. And, like tea, it can trace its roots back to China, where pottery vessels, which date to 7,000 BC, show evidence of having held a fermented alcoholic drink made from grapes, rice and various other ingredients.

However, The Philosophy of Wine has narrowed its focus to wine made purely from grapes, the first evidence of which comes from a site in the Caucasus Mountains, dating from 6,000 BC. And, as Ruth Ball points out, this is only the oldest site found so far, which means that given how little survives from that time, humans were probably making and drinking wine long before that. So, I think it’s safe to say that wine has a history going back at least 8,000 years.

There are seventy species of grapevine growing worldwide today, but the book’s focus is Vitis vinifera, which grows wild along the shores of the Mediterranean from Spain right across to the Mediterranean’s eastern extent and beyond to the southern shore of the Black and Caspian Seas.

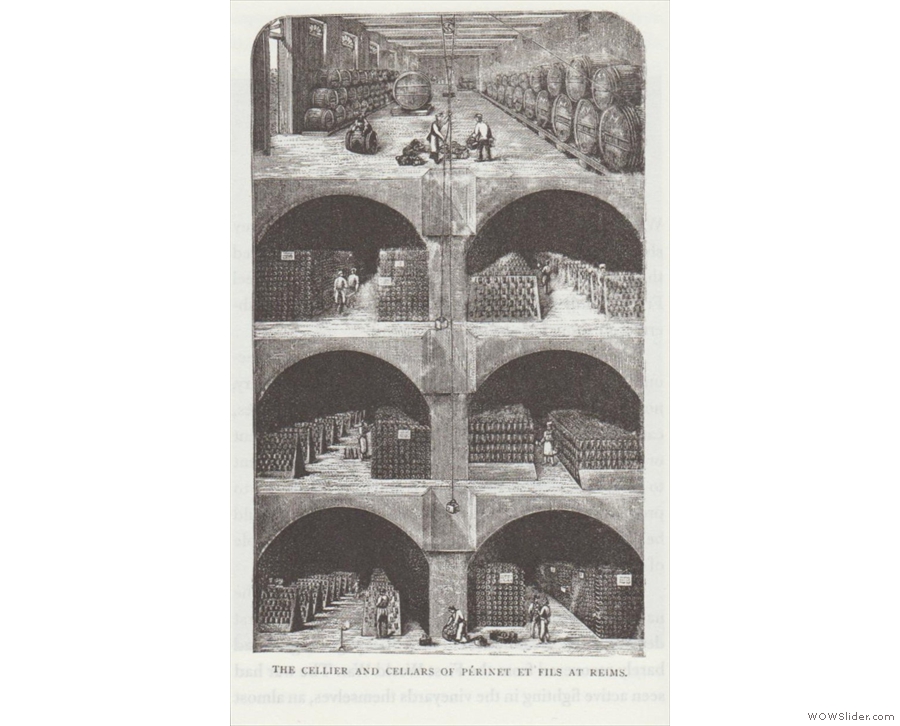

Initially, wine was stored in the amphora, a large clay jar that was ubiquitous in Greek and Roman culture. A major technological breakthrough came in the first century BC when the Celts invented the wooden barrel and used it for storing wine, which brought about significant changes. The amphora is airtight, which means that wine can be stored for long periods in amphorae, during which time it ages. In contrast, barrels allow in small amounts of air, which, over time, means the wine turns to vinegar. Thus the art of aging wine was lost for over 1,500 years until the invention of the thick, dark glass bottle in the middle of the 17th century. This is how we store wine today and, along with the invention of the cork (and corkscrew) means that once again, wine can be stored in airtight conditions and the art of aging wine was rediscovered.

All of this is covered in the opening chapters of The Philosophy of Wine, after which Ruth Ball takes us through some selected nuggets of wine’s rich history. This includes the invention of Champagne (initially bubbles in Champagne were considered an impurity and the early pioneers worked hard to get rid of them until the English developed a taste for it) and fortified wines such as my favourite, port, and Madeira.

From there, The Philosophy of Wine devotes chapters to wine growing in Australia (a tale of law-breaking, mostly by the authorities rather than the convicts that one stereotypically associates with Australia’s early settlers) and California, which brings us to the subject of the next chapter, the great wine blight. Like coffee, wine growing is a worldwide monoculture, making it very susceptible to pests and disease.

It was the spread of wine to America that nearly brought about the downfall of the Old World vineyards, with new diseases being returned across the Atlantic. The first was a fungus which spread remarkably quickly: three years after its first appearance in 1851, every vineyard in France was infected. This was treated by the application of sulphur and, just as quickly as it came, it was eradicated, with French vineyards largely free of disease by 1858.

Only four years later, an even greater threat emerged, caused by microscopic insects now known as phylloxera. However, it took a long time for the cause to be identified and even then, no-one was sure how to combat it, with two rival factions pushing opposing solutions. One side advocated treatment with sulphur, while the other, which eventually triumphed in 1887, advocated grafting vines onto the root of an American species which was resistant to phylloxera. Today, with the exception of Chile, which has no phylloxera infection, all commercial vineyards grow grafted vines.

We’re now approaching the end of The Philosophy of Wine. One chapter is devoted to the efforts of the French vineyards to resist German occupation in the Second World War, while the final chapter looks at the future of wine and, in particular, how vineyards might respond to rapid climate change, which could devastate traditional wine growing regions such as France.

I learnt a lot from such a small book and, as an entertaining introduction to the world of wine, I highly recommend The Philosophy of Wine.

Don’t forget that you can share this post with your friends using buttons below, while if you have a WordPress account, you can use the “Like this” button to let me know if you liked the post.

1

1 2

2 3

3 4

4 5

5 6

6

Pingback: The Philosophy of Tea | Brian's Coffee Spot

Pingback: The Philosophy of Gin | Brian's Coffee Spot