Welcome to the third and final part of my exploration of traditional Vietnamese coffee following my recent visit to Vietnam. Part I covered my introduction to Vietnamese coffee and the traditional cà phê phin, a cup-top metal filter. I explained how, after a few false starts, I discovered a taste for speciality coffee made with the cà phê phin when I tried it at Shin Coffee in Ho Chi Minh City.

Welcome to the third and final part of my exploration of traditional Vietnamese coffee following my recent visit to Vietnam. Part I covered my introduction to Vietnamese coffee and the traditional cà phê phin, a cup-top metal filter. I explained how, after a few false starts, I discovered a taste for speciality coffee made with the cà phê phin when I tried it at Shin Coffee in Ho Chi Minh City.

In Part II, I continued my exploration, trying traditional Vietnamese coffee, both speciality and non-speciality, over ice, and with condensed milk, with mixed results. I also tried the (in)famous egg coffee, traditional Vietnamese coffee with a layer of whipped egg yolk and condensed milk. Think of it as a liquid pudding rather than coffee and you’ll be fine.

In this, Part III, you can see how I got on making traditional Vietnamese coffee in various hotels and back at home using my own cà phê phin which I bought at The Espresso Station in Hoi Ann. I’ve tried a number of different beans, and used a couple of recipes which I picked up simply by observing baristas making coffee at the likes of Shin Coffee and Hanoi’s The Caffinet.

You can see how I got on after the gallery.

Let’s start with a simple explanation of the cà phê phin, the cup-top metal filter (although you can get ceramic versions) which is used to make traditional Vietnamese coffee. If you’re ever in Vietnam, I suggest you get one: most good coffee shops will sell you one for under £1. In the end, I came away with three of them, partly because they were so cheap. In the process, I discovered that there are a couple of different designs. A word of caution though: all three that I bought were metal and lightweight, which means that they can bend/dent in transit if you’re not careful. I wasn’t and have already had to push one back into shape!

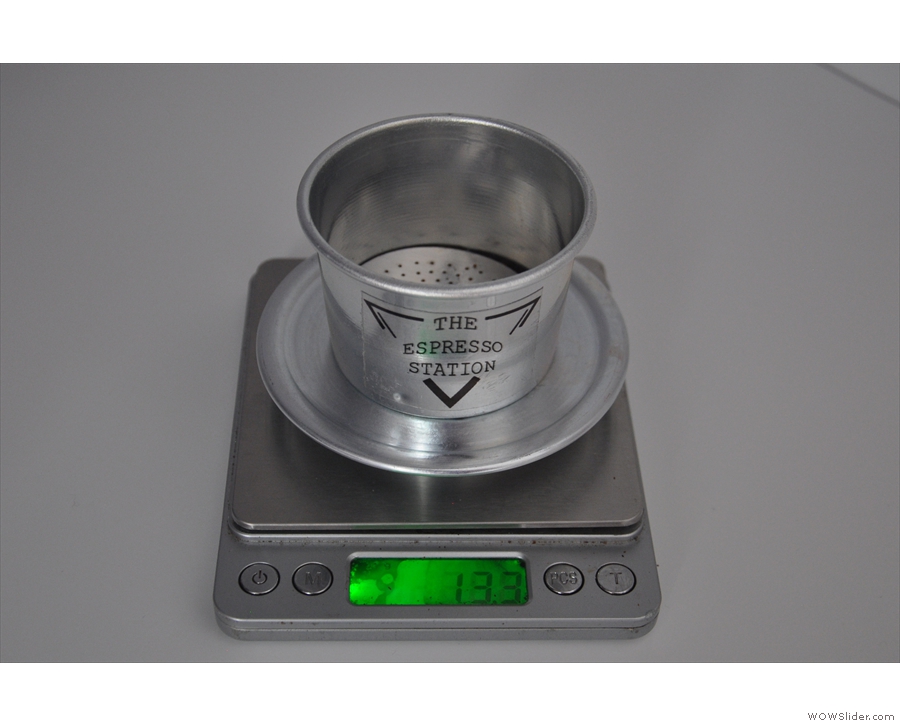

My main cà phê phin is the one I got at The Espresso Station (this is the one you’ll see in all the photos). It consists of four parts:

- a circular base with a coarse metal filter in the centre

- a cylindrical body, with another coarse metal filter at the bottom

- a third, coarse metal filter, with a handle, which fits inside the body

- a metal lid which fits on top of the body

The other design I came across combines the base and body into a single unit. As a result, this only has one filter at the base, which dramatically alters the way it works, something which I’ll talk about later on.

When it comes down to it, the cà phê phin is a pour-over method, akin to the V60, Kalita Wave or Chemex. You put the ground coffee in the body of the filter, pour water over the top, and the coffee comes out the bottom. However, there are some important differences, not least with the type of coffee being used. Whereas for a typical pour-over, I’d go for a medium or light-roast single-origin, for traditional Vietnamese coffee, a dark roast or espresso blend is used, often with a large amount of Robusta. For this reason, I’ve tended to use espresso blends myself, although I’ve also had success with a medium-roast Vietnamese single-origin.

The most striking difference comes with the weight of coffee/volume of water used. Whereas a typical pour-over will use a dose of 15g of ground coffee to get 250ml of coffee, the main recipe I use results in much shorter drinks of around 80ml for a dose of 20g of ground coffee. It’s also a slow process: a typical pour will take five minutes, with the coffee literally dripping out of the bottom of the filter.

It can be a bit disconcerting to start with, as the first drip will often take up to 30 seconds to appear. There is also, as I discovered, a very fine margin for error, so I recommend filtering your coffee into a glass so that you can keep an eye on progress!

When it comes to water, during my travels, I used water that was just off the boil. Typically, I’d boil my kettle, then pour the water into my metal jug to reduce the temperature by a few degrees, then pour from my jug into the filer. Back home, with my temperature-controlled Gooseneck Kettle, I tend to go for my default pour-over temperature of 94⁰C.

The basics dealt with, you can see how I got on actually making coffee after the gallery.

My go-to recipe for traditional Vietnamese coffee is the one I learnt at Shin Coffee, where I had my first traditional Vietnamese coffee made with speciality beans. It would be unfair on Shin to say that I was taught this recipe: I picked it up through a combination of observation and questioning.

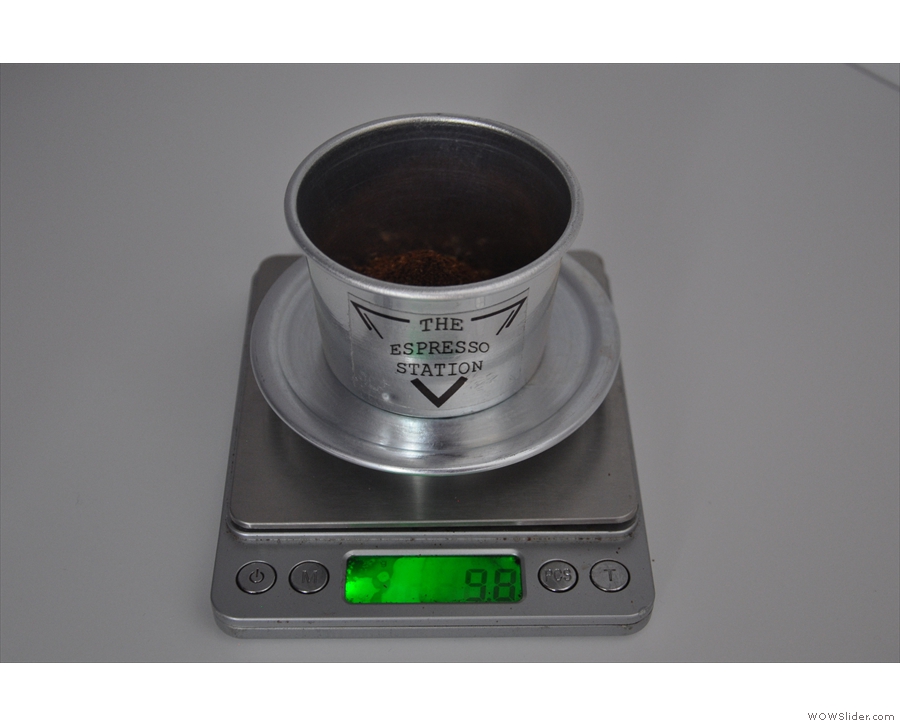

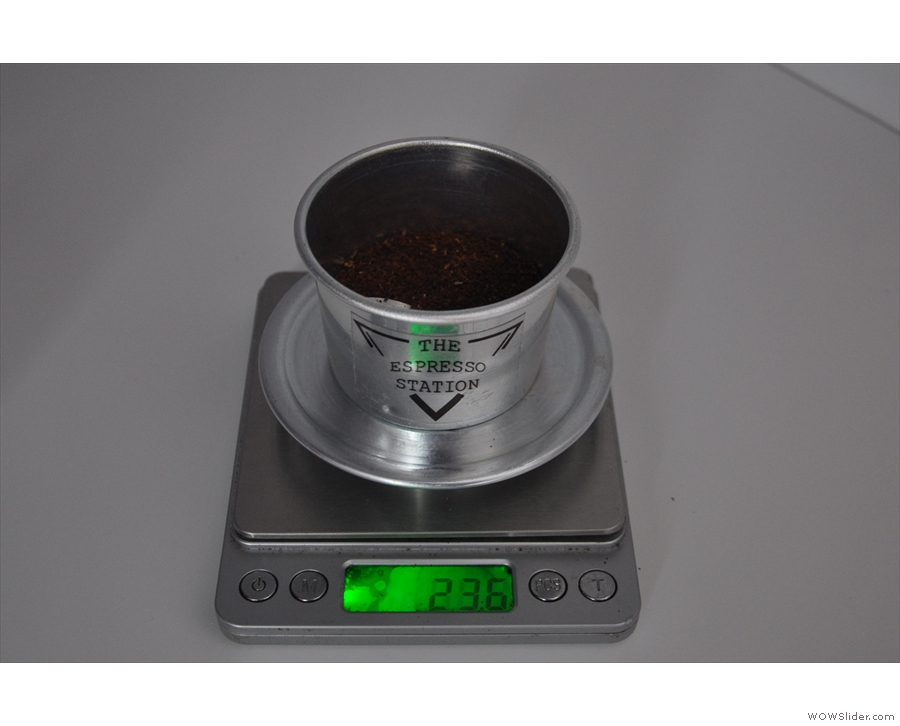

After I’d bought my first cà phê phin at The Espresso Station in Hoi An, I went back to my hotel and made my first cup of traditional Vietnamese coffee. I started with 20g of Panther Coffee’s West Coast espresso blend, ground using the same setting as I’d use for my cafetiere. I pre-rinsed/warmed my cà phê phin, then put 10g of coffee in the bottom. Next, I put the third filter on top of the coffee and pressed it down (when I first saw this being done at Shin, I thought it was being tamped, not realising that the filter was left in the body of the cà phê phin. Finally, the remaining 10g of coffee is poured on top and the whole ensemble shaken to level out the coffee.

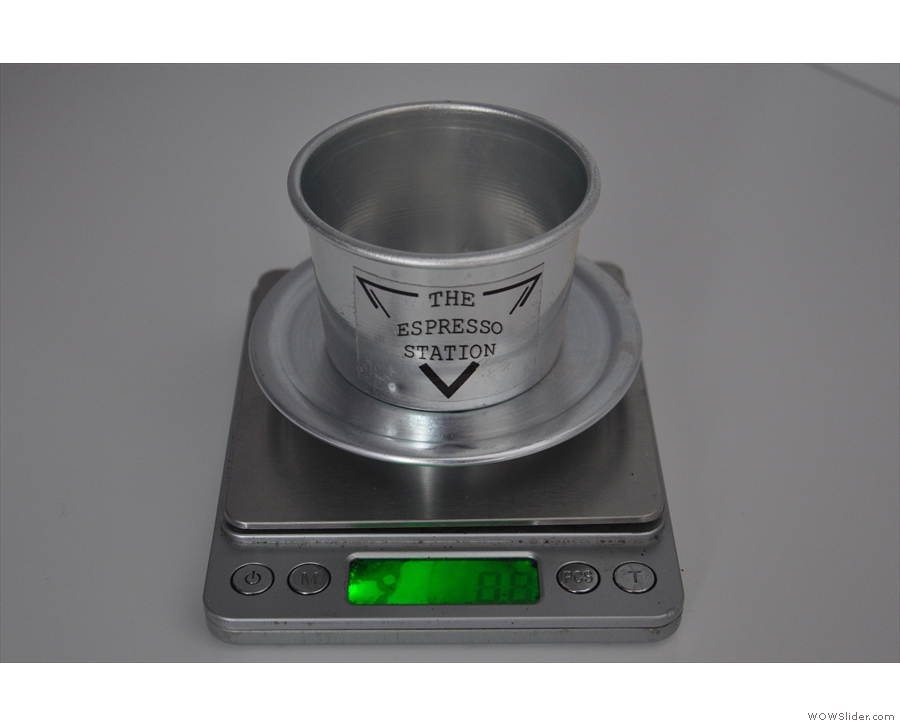

Put the assembled cà phê phin on a pre-warmed glass, put the whole lot on your scales, then zero them and we’re ready to go. If you don’t have scales, don’t worry, you can easily wing it.

Just as for any pour-over, you want to make a first pour to let the coffee bloom. I aim for 40g of water for this, leaving it stand for about 30 seconds. At this point, it’s likely that nothing will have dripped through (at most you can expect a drip or two). Although the coffee is fairly coarse, the combination of three filters and a deep bed of means that it takes the water a long time to filter through.

The second pour should fill the cà phê phin up to the top (if you’re not using scales). Alternatively, you are looking for a total weight of 120g. Pour as you would for any pour-over: continuous, steady and, if you can, moving the pouring-point around the surface of the coffee. Once you’re reached the top/hit the correct weight, stop.

By now, the coffee should be filtering through. I say filtering, although dripping is more accurate. At no point should the coffee being pouring through the filter. At this point, you can put the lid on the cà phê phin, although I like to watch the coffee filtering through. I’m not sure what the point of the lid is: it might simply stop things getting into the coffee, or it might help keep the heat in. Whatever the reason, if you’re in a coffee shop, there’s a good chance your coffee will be brought to the table, the cà phê phin, lid on, sitting on top of the cup/glass.

Just wait until it filters through and then make use of another of the cà phê phin’s useful features: take the lid off, turn it upside down and place the base and body of the cà phê phin on the lid. This is great because it means that the lid will catch any overspill if there’s still a little bit of water left to filter through. A word of caution though: if your cà phê phin is all metal, it will get very hot, so try not to burn your fingers when you lift it off!

Back to my hotel room and I left the coffee to filter for a total of five minutes before taking it off the glass and putting it on the lid. At this point there was still a little bit of water left to filter through. Opinions will vary on this and some will always say to let all the water filter through, but I’ve never done that, even with traditional pour-over, where I find the last of the coffee tends to be over-extracted.

You can see what the resulting coffee was like after the gallery, where you can also find out how I successful I was with my subsequent attempts.

For a first attempt, my coffee was pretty much spot on. I’d followed the recipe, it has filtered for five minutes (the time recommended at Shin) and I’d got 80g of coffee out. Best of all, it tasted pretty good, not quite as naturally sweet as the coffee I’d had at Shin, but extremely drinkable nonetheless. Piece of cake, I thought.

My next few attempts were nowhere near as successful. I thought I’d repeated the process step-for-step, the only difference being that I was at a different hotel (Hué rather than Hoi An). The first two attempts were pretty disastrous, with the coffee flooding through in a couple of minutes. The results were drinkable, but nowhere near as good as my first attempt.

To counter this, for my next attempt, I dialled the grind right down from cafetiere to Aeropress. This, however, was even worse, the resulting coffee dripping through so slowly that I aborted the attempt at eight minutes, the end result being undrinkable. By now I was in Hanoi and, beginning to think I’d never get it right, I’d switched to my default pour-over grind, which is roughly halfway between cafetiere and Aeropress on my grinder.

To my surprise, this worked, and suddenly I was back to five minute extraction times, using roughly 120g of water in and getting 80g of coffee out for a 20g dose. I continued with this recipe at home, where I started using the 70/30 blend I’d bought at Oriberry Coffee. Once again, I was successful and that’s pretty much my default recipe now. More recently, on my current trip to Madison, I’ve been using the La Viet single-origin beans I picked up in The Caffinet, again with the same recipe and again meeting with success.

While I’ve been enjoying the resulting coffee, it’s my least favourite of the three beans I’ve used and also the lightest roast. In this respect, I tend to go with the Vietnamese and prefer to use an espresso blend, the cà phê phin not really bringing the subtly of the coffee out. In contrast, I’ve also been running the La Viet through my Aeropress, which does a far better job of highlighting the coffee’s more subtle flavours.

Talking of The Caffinet, this is where I learnt my second recipe, which, as you will see after the gallery, was to come in very useful when I got home.

I ordered a traditional Vietnamese coffee over ice at The Caffinet on my last day in Vietnam. The barista made the coffee, but used a very different approach and recipe than I was used to. Rather than the 20g dose I had been using the dose was 10g, which was put into the bottom of the main body of the cà phê phin. A total of 100g of water was used and while the basic process was the same (first pour to allow the coffee to bloom, then the main pour), the coffee filtered through much more quickly, resulting in a shorter extraction time. Also, the barista stirred the coffee towards the end, the first time I’d seen anyone stir a cà phê phin.

The resulting coffee (which I tried hot) was much more like a traditional pour-over in both taste and consistency. I haven’t had a chance to try the recipe with the La Viet single-origin beans I got at The Caffinet, but I suspect that it would suit them as a method. If I do, I will be sure to let you know how I get on.

However, I did find the recipe useful on a couple of occasions. When I left my hotel in Hanoi later that day, the staff gave me a gift: a bag of coffee. Now, I don’t know if everyone who stays there gets a bag of coffee, or whether they’d seen my cà phê phin (which I’d left out on the dresser in my room) and decided to get me coffee. Either way, it was a very thoughtful gesture.

The coffee was from Trung Nguyên, Vietnam’s largest coffee brand. More importantly, it came pre-ground and when I got it home, I tried it out using my traditional recipe. It was a disaster: the coffee was far too finely ground for the three filters and almost nothing got through. A quick rethink was required and, recalling the recipe from The Caffinet and its much shorter extraction times, I improvised.

I did away with the third filter and simply replicated The Caffinet’s recipe, using 10g of coffee and 100g of water. The resulting extraction time was closer to five minutes than two, but the important thing was that it worked. The coffee extracted well and the resulting brew was very drinkable. I did it a couple times more to check that it wasn’t a fluke and each time it worked nicely, although I have to say that the actual coffee, a rather sweet, syrupy mixture that had a hint of vanilla, was not to my taste.

The other time recipe came in handy was with my third cà phê phin. I’d bought this as a gift for my friend Marc at Oriberry Coffee. When I got it out of the packet to show it to Marc, I realised that the base plate and body were a single unit, so it only had one filter at the bottom. Fearful that this meant that the coffee would extract too quickly, I fell back on The Caffinet’s recipe, using the internal filter (the one that fits inside the body of the cà phê phin as a second filter and putting the coffee (10g again) on top of that.

I ground the coffee (Oriberrry’s 70/30 blend) for pour-over and, using 100g of water, got a pretty decent extraction, this time coming out at about two minutes. Even better, the resulting coffee tasted pretty good!

In conclusion, what to make of it all? Well, the first thing is I like the cà phê phin as a preparation method, much to my surprise. It can be fiddly and it takes a bit of getting used to, but I found that once I’d nailed the recipe, it made very drinkable coffee. More importantly, the coffee tastes very different from any other method I have, giving me another way of making coffee. If coffee through the cà phê phin tasted the same as through the cafetiere, for example, it really wouldn’t be worth the effort.

Like any other method, I’d urge you to use the recipes presented here as a starting point and experiment, finding what suits you. Note that like most other pour-over methods I’ve used, the cà phê phin is very sensitive to grind size and is very unforgiving. Unlikely my Aeropress or cafetiere, where I can get the grind size off by a notch or two and not really change the coffee too much, it has a huge effect with the cà phê phin, which can be frustrating, particularly when changing beans.

Ultimately though, experiment. Find a method and recipe that suits you and remember the golden rule: if you are making coffee you like, then you are doing it right.

If you liked this post, please let me know by clicking the “Like” button. If you have a WordPress account and you don’t mind everyone knowing that you liked this post, you can use the “Like this” button right at the bottom instead. [bawlu_buttons]

Don’t forget that you can share this post with your friends using buttons below.

1

1 2

2 3

3 4

4 5

5

1

1 2

2 3

3 4

4 5

5 6

6 7

7 8

8 9

9 10

10 11

11 12

12 13

13 14

14 15

15 16

16 17

17 18

18

1

1 2

2 3

3 4

4 5

5 6

6 7

7 8

8 9

9 10

10 11

11 12

12 13

13 14

14 15

15 16

16 17

17 18

18 19

19

1

1 2

2 3

3 4

4 5

5 6

6 7

7 8

8 9

9 10

10 11

11 12

12 13

13 14

14

Pingback: The Espresso Station | Brian's Coffee Spot

Pingback: Oriberry Coffee, Hàng Trống | Brian's Coffee Spot

Pingback: Vietnamese Coffee Part II | Brian's Coffee Spot

Pingback: Chatei Hatou | Brian's Coffee Spot

Pingback: Vietnamese Coffee Part II | Brian's Coffee Spot

Pingback: Making Coffee at Home: AeroPress | Brian's Coffee Spot

Pingback: Making Coffee at Home: Espresso | Brian's Coffee Spot

Pingback: Brian’s Travel Spot: Danang, Hội An and Huế | Brian's Coffee Spot

Pingback: Brian’s Travel Spot: Huế to Hanoi | Brian's Coffee Spot

Pingback: Phin Coffee House | Brian's Coffee Spot

Pingback: Meier’s – Vietnamese Speciality Coffee | Brian's Coffee Spot

Pingback: 2022 Awards – Best Filter Coffee | Brian's Coffee Spot